One and a half hours south of Tucson sits a wide expanse of yellow grasses, gnarled trees, low lying shrubs, and chunky rock as far as the eye can see. Riding our gravel bikes through the dirt backroads of the Buenos Aires Wildlife refuge was a lesson in Sonoran ecology. It wasn’t long before clipping in that we spotted life in the desert— lots of it! Mule deer, cottontails, and countless birds and lizards appeared on the scene, some apathetic, some curious of our mechanical fun. Each animal encounter was without fanfare, a mere acknowledgement of the other’s presence sans fear or reproach. In that space, we were each of us no more than patrons of the land — them on hooves and paws and claws, and us on bikes.

It’s a wonderful freedom, to feel your place in the world like this. (I suppose it’s not for everyone though; finding oneself insignificant in the bigger picture can easily also give rise to anger or shame, a need to make oneself matter.)

As we rode, we encountered up close what had at first appeared to be a thick shadow upon the distant mountain side. Coming face to face with the wall, we were at first bewildered — impressed, even — by the sheer scale of the thing, and then by the awkwardness of the project — how misplaced it was amidst the wild expanses of the Sonoran desert.

Closer inspection of the imposing collection of iron plates and bars revealed discomforting details: barbed wire marking off not just the wall but a healthy margin around it as well, narrowly spaced bars that prohibit living things of all species larger than a jackrabbit from passing through, hardy desert flora cleared and land compacted to produce a wide dirt road on which police cars could drive to patrol the perimeter, and a construction site frozen in time, having not yet succeeded in blasting through a mountain to erect a manufactured boundary where natural topography had failed to comply.

The mid-morning heat rises quickly in the desert. We couldn’t linger for much longer. Turning our backs on the wall, we rode back into the dirt, into the grass, away from the ugly scar on the mountain side, now looming in the backdrop. The silent enforcer. Keeping not only us, but the American deer, over here; not only them, but the Mexican jaguars, over there.

These wildlife refuges are some of the last places in the country that are designated for protection and conservation. Shouldn’t we protect them?

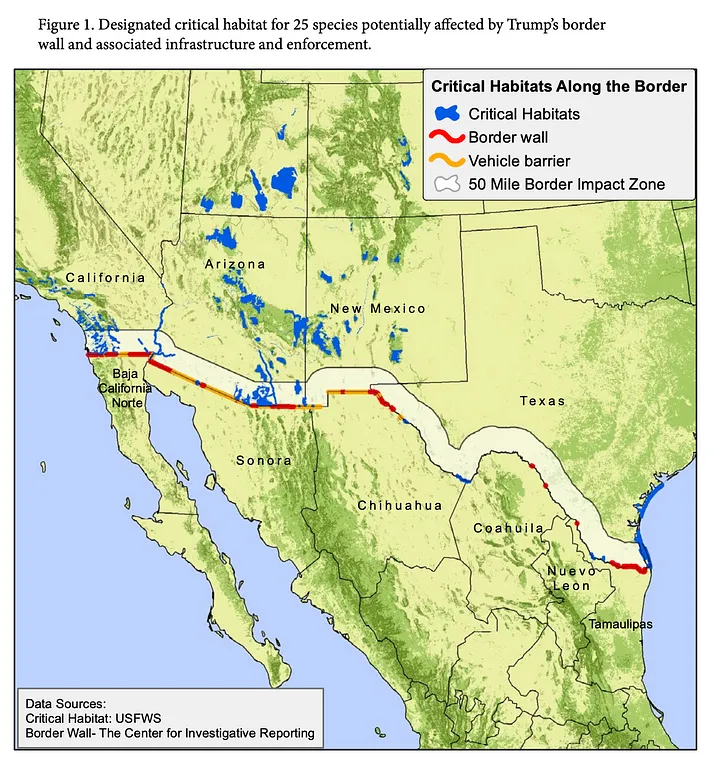

The borderlands between the US and Mexico aren’t a monolith, and they aren’t empty wasteland. They cover desert, mountain, and subtropical regions. They’re home to hundreds of rare species, including nearly 100 endangered species like ocelots, Mexican grey wolves, and bighorn sheep. With wall construction destroying sensitive ecological habits, contributing to noise, light, and air pollution, and drying up natural springs due to high water utilization, we may soon yet make a reality the lifeless image of the desert born of Hollywood imagination.

Buenos Aires is just one of 5 wildlife refuges that the border wall disrupts, especially in its sly and strong growth during COVID before Biden halted construction in January of this year. In even just this small stretch of refuge, the ostentatious border wall display made me wonder, what wildness? Whose refuge? What’s next?

A 30 foot steel wall blazing through wildlife corridors feels like just another example of how issues of human rights and environmental protection go hand in hand. Often we ignore one for the other. Sometimes both lose.

For more information and to take action, check out these and other resources available online:

- https://defenders.org/wall

- https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/campaigns/border_wall/

- https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/endangered-species-are-casualties-trump-s-border-wall

- https://www.voanews.com/science-health/threats-wildlife-persist-even-us-halts-border-wall-construction

- https://wildlandsnetwork.org/blog/the-border-walls-cascading-impacts-on-wildlife/

- https://earth.stanford.edu/news/how-would-border-wall-affect-wildlife

- https://www.audubon.org/magazine/winter-2020/the-border-wall-has-been-absolutely-devastating

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/border-wall-arizona-to-have-tiny-animal-openings